|

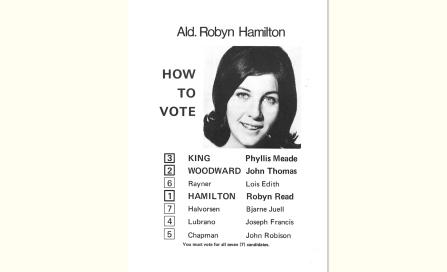

Resident actionThe Resident Action movement in Sydney is generally associated with the often dramatic protests against development and demolition in the 1970s.Best known are the Hunters Hill residents who saved the remnant bushland called Kelly’s Bush from town house development, and the coalition of residents and sympathetic trade unionists who stopped the wholesale demolition of Georgian and Victorian-era buildings in the Rocks through a new tactic called the ‘Green Ban’, whereby organised labour in the form of the Builders Labourers’ Federation prevented site work. However, activism by residents intent on preserving the amenity of their neighbourhood has a longer history in North Sydney. In 1911 the Bay Road Progress Association formed to fight the completion of the Oyster Cove Gas Works in Balls Head Bay. Association members had bought into the Berry Estate subdivisions on the understanding that ‘noxious’ trades were to be excluded from their area. However, in 1906, while those subdivisions were being released, the Berry Estate trustees returned foreshore land to the State government which then leased part of Balls Head Bay to the North Shore Gas Company. The residents failed in preventing the Gas Works but succeeded in having the adjacent bushland on Berry Island declared a park in 1926. In the 1950s, the nuisance of industrial development motivated the McMahons Point and Lavender Bay Progress Association to oppose the industrial zoning of the Berrys Bay and Lavender Bay foreshore – a classification which in large part simply recognised the long history of timber storage, boat building and wharfage there. Though the bays had long been an important part of the working harbour, a 1956 residents’ petition argued that McMahons Point was ‘one of the beauty spots of Sydney’ and should be given over exclusively to residential use. Estelle Hillard was one of the campaign’s leaders. Her work ultimately led to her election to Council as the first female ‘alderman’. The campaign for rezoning was successful. As part of its push for overturning waterfront industrial zoning, the Progress Assocation enlisted the support of the high profile architect Harry Seidler. His residential scheme for the area, in turn, led to the construction of ' Blues Point Tower' in 1962 – then the tallest block of flats in Australia. Ironically, it was the development of large flats such as 'Blues Point Tower' that prompted the other major issue motivating resident action – the impact of high-rise. By 1960, the North Sydney Homes Protection Group was arguing that such development in newly rezoned areas risked overshadowing existing homes and exacerbating traffic congestion. The Cremorne Foreshore Protection League, led by Dr Claire Weekes, opposed the construction of high-rise in that area because of the threat to views. Campaigns about specific developments were won and lost but, in 1960, Council agreed to consult with ‘neighbours’ affected by flat development before approval was given. The watershed 1971 Council election was fought, in large part, over the issue of flat development. It ushered in ‘a new breed’ of Councillors who were typically young, tertiary-educated, and determined to preserve the characteristics of the localities that had attracted them to North Sydney. Tony Salier ran in the East Ward then representing North Cremorne on a ticket that promised ‘a complete ban on further high rise development in the ward’. Faced with the prospect of having flats built opposite him, he 'decided that the only way to stop all this was to get inside and get the plan changed'. (Merle Coppell Oral History Collection OH228). Robyn Hamilton (now Read) had lived in North Sydney for most of her life but, after moving to Wollstonecraft with her young family, helped to establish the Wollstonecraft Resident Action Group opposing medium and high density development. In 1971 Hamilton, John Woodward and Phyllis King, were endorsed by the North Sydney Homes Protection Group, Kirribilli Progress Association, and Neutral Bay Civic Amenities Association because of their stand against high-rise. When elected, Hamilton and King were part of the growing number of women who followed in the ‘footsteps’ of Estelle Hillard. In Robyn's words, 'It was all a really powerfully based women's movement and, in some ways, I think it was our version of the women's movement'. Audio: Listen to Robyn (Hamilton) Read explain her decision to run for Council in 1971; interviewed by Margaret Park in 2000. Merle Coppell Oral History Collection, OH226

|

|