|

|

||

|

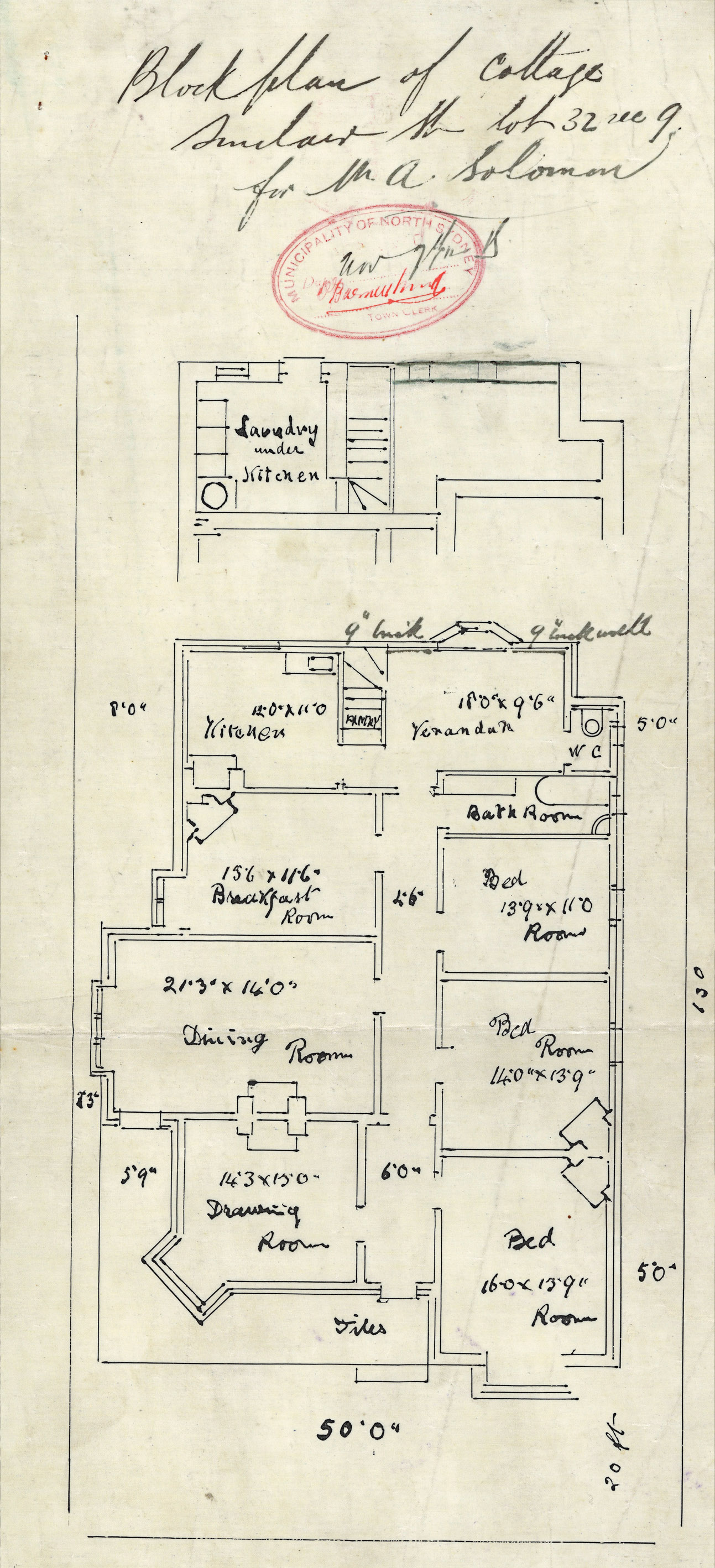

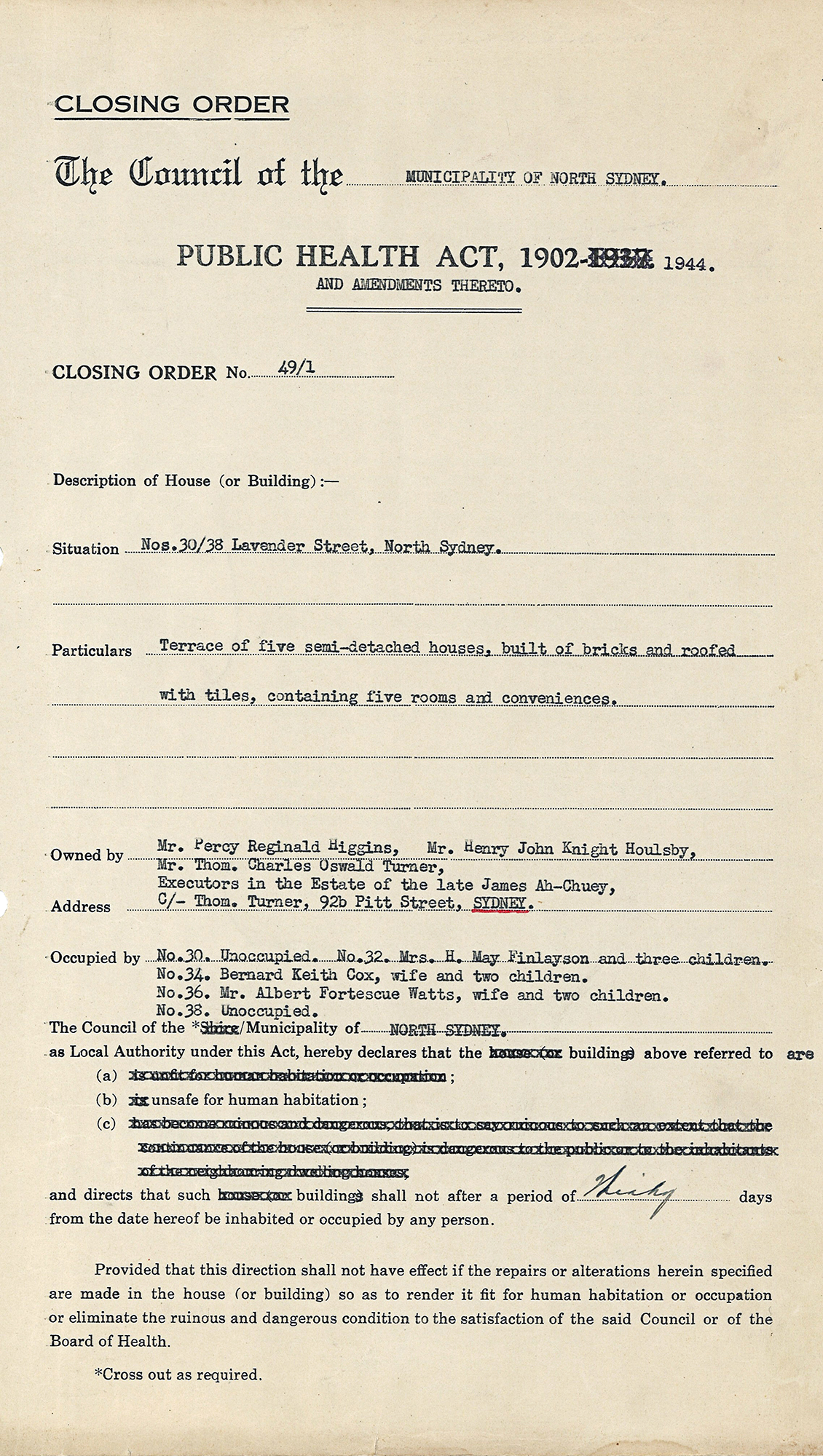

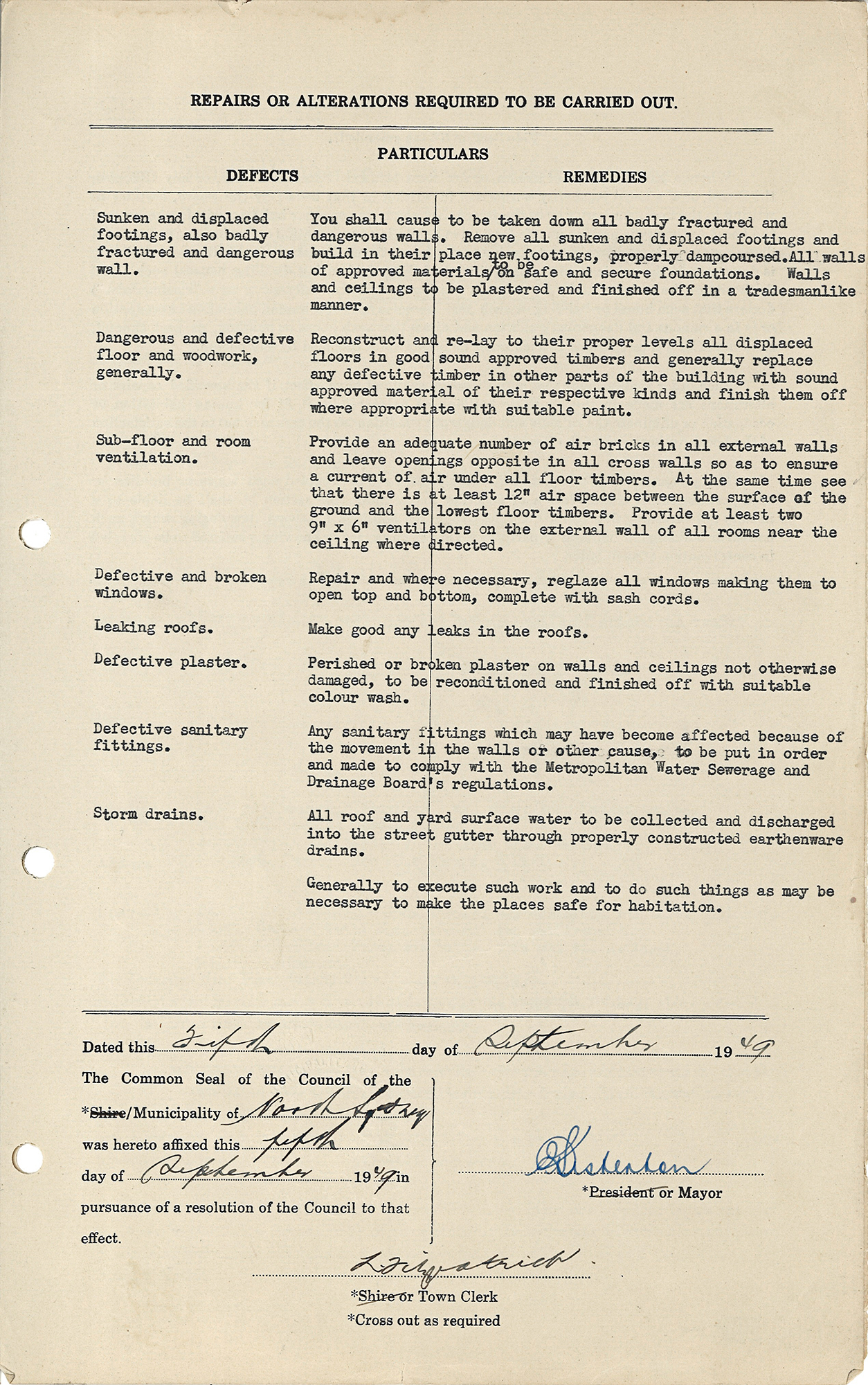

Health and Building RegulationsBefore the establishment of local government, there was virtually no regulation of building activity and no control of public health in North Sydney.People simply erected houses on their blocks of land, with or without the assistance of an architect or trained builder. With the creation of the Boroughs of East St Leonards in 1860, St Leonards in 1867 and Victoria in 1871, funds from property rates and government subsidies became available for public works, as did a more effective means of petitioning the government for the same purpose. In 1890, when these Boroughs amalgamated to form North Sydney Council, local government was inspecting and attempting to remedy health nuisances such as sewage spills, watering unsealed roads to minimise dust, constructing gutters along roads and contracting for the removal of ‘night soil’ – human waste – from the pan toilets that were commonly used before the completion of the sewerage system in 1898. Free garbage collection, for rate payers at least, was introduced in the mid-1890s. By then there was a general concern with the conditions of city life in Australia. The spectre of Dickensian London fuelled local fear of congestion, crowding, lack of fresh air, space and sunlight. For, despite a well-established national mythology that celebrated 'the bush' and 'the outback', Australians were in large part an urban, or at least suburban, people. With the 1906 Local Government Act, councils received regulatory powers over the erection of buildings ‘as to height, design, structure, materials, building line, sanitation, the proportion of any lot - which may be occupied by the building or buildings to be erected thereon’. The earliest building applications that survive in North Sydney Council’s archives date to 1909. These sometimes included house floor plans, albeit often rudimentary, that specified the size of dwelling and the type, number and dimension of rooms. The Local Government Act that followed in 1919 reflected the growing enthusiasm for town planning. With better understanding of disease and infection came the desire to improve the quality of the living environment generally. Planning powers were granted to Councils so that, among others things, noxious trades could be kept away from dwellings through zoning. Accordingly, residential districts were created around Lavender Bay, without affecting existing working waterfront areas, in 1923. Council already had responsibilities and powers to monitor disease under the Public Health Act of 1902. These included house calls by Council’s Sanitary Inspector and reporting to the Office of the Medical Officer in Health for the Metropolitan Combined Sanitary Districts. In 1913, for instance, the Inspector went to a wooden cottage at the ‘rear of Gerard Street’ where two bedrooms were occupied by three adults and five children. Neither bedroom was ventilated. The Medical Officer advised Council to serve notice to the owner to provide adequate ventilation - probably windows - and have the house connected with the sewerage system. In 1949 the Health Act permitted Council to declare the terrace of five dwellings at 30-38 Lavender Street to be ‘unfit for human habitation’. The extensive list of defects included crumbling walls and rotten floors. That two of the five houses were unoccupied during that time of severe housing shortage after World War Two is testimony to the condition of the dwellings. Councils had recently been given the power and responsibility to formulate town plans under the Town and Country Planning Act of 1945. The North Sydney Planning Scheme Ordinance was finally gazetted in 1963. In the meantime, North Sydney Council had challenged the rulings of the Cumberland County Council which existed as an overarching planning body from 1945-1963. That Council held that much of the area around Lavender Bay was industrial, despite North Sydney's earlier local zoning to the contrary. The ultimate overturning of the industrial zoning resulted in the construction of 'Blues Point Tower' in 1962. The height of that block of flats, then the tallest in Australia, was made possible by the passage of the Height of Buildings Amendment Act of 1957 which removed the 150 foot restriction that had been in place since 1912. The mushrooming development of high-rise flats confronted Council with the difficulty of controlling the size and location of the buildings, particularly in the face of resident action against over-development. The several Flat Codes introduced through the 1960s did little to forestall the complete re-characterisation of large swathes of Kirribilli, Wollstonecraft and Neutral Bay. By the end of the 20th century considerations for allowable local development, including health, amenity and heritage, were complex. Council’s current policies are determined by the 2013 Local Environment and Development Control Plans. |

|