|

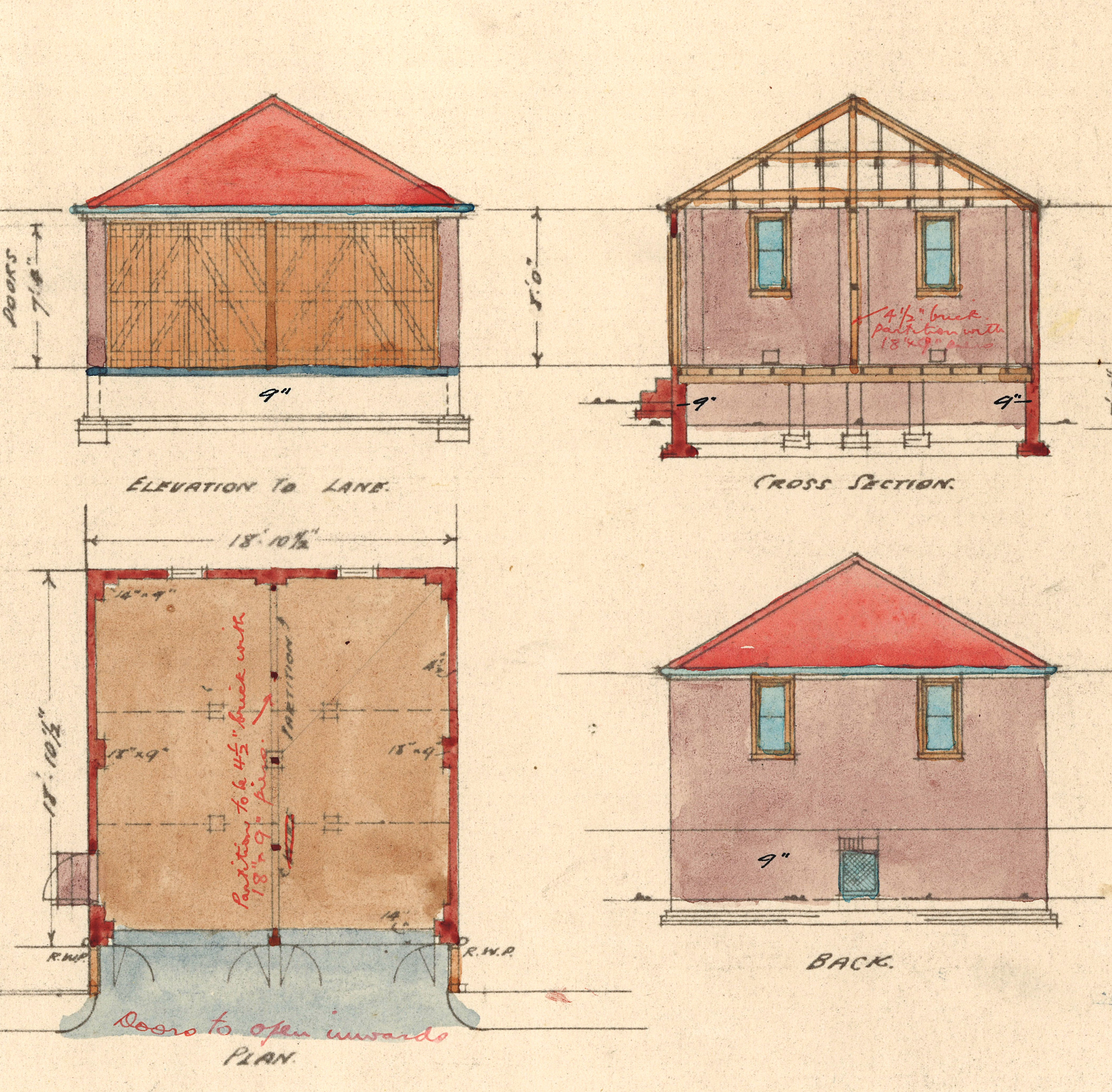

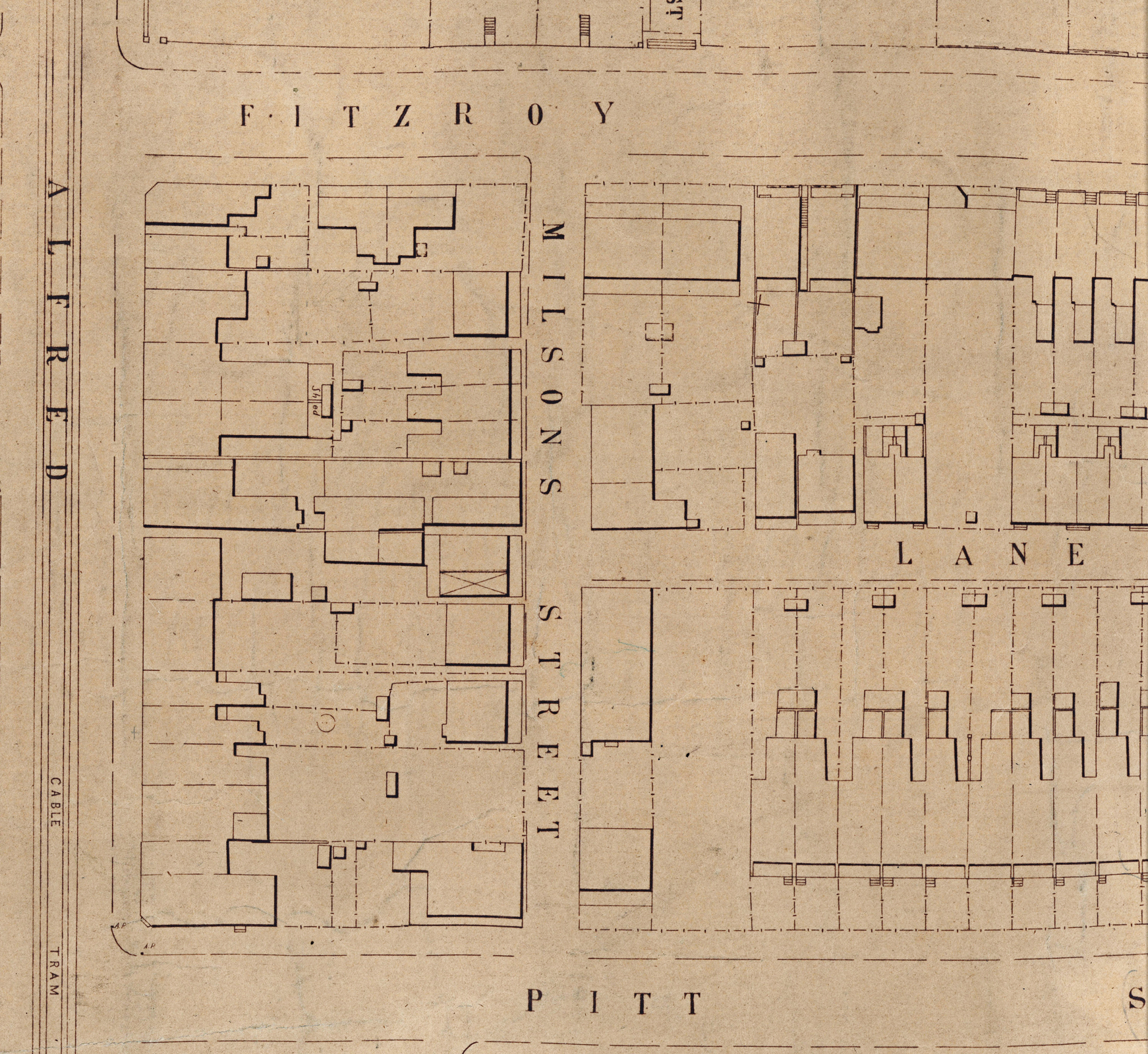

TransportThe location of dwellings in North Sydney has been influenced by the need to access transport ever since people have lived around the harbour.Proximity to the waterway was important for Aboriginal people because it allowed relatively easy travel, as well as providing food. Most evidence of their presence has been found in rock shelters close to the water. Canoes, called nawi by the harbour clans, were routinely pulled up on the harbour’s sandy beaches ready for use. With the notable exception of ‘Crows Nest Cottage’, the first dwellings built by Europeans sat close to the water to improve access to the town on the south side. ‘Thrupps Cottage’ at Neutral Bay was not unique in having its own timber jetty. Not surprisingly, ‘Billy Blue’s Cottage’ was situated near the waterway for its owner was one of the first watermen on the harbour. Blues Point consequently became the main point of departure and arrival for those crossing the harbour. And when steam ferry passage was offered in the mid-1840s, it was to Blues Point that the vessels ran. The thoroughfare that ran north from there was the first in the area. It was gazetted as a road in 1838. When the colonial Surveyor General, Thomas Mitchell, prepared his topographical map of the harbour in 1853, he was careful to include the cluster of buildings that gathered around the road, close to the water. Land journeys along thoroughfares like this were undertaken on foot or by horse for professional carriers and the affluent. Private ownership of a horse was costly, not least because one needed to accommodate the animal. Most large homes on suitable blocks, such as ‘Brisbane House’, had stables or even a coach house. By the early 20th century, keeping a horse may have better reflected the leisure pursuits of the wealthy than their transport needs. ‘Brent Knowle’, built in 1914, was not alone among large houses of its era in having a coach house included alongside a car garage. By the end of the 19th century proximity to the harbour, and jobs on the south side or on the waterfront itself, was at a premium. Then, the main North Sydney ferry stop was at Milsons Point, where the grand barrel-roofed terminal was a harbour landmark. The streets around became the most densely settled in the municipality. Accordingly, spatially efficient terrace housing lined the streets of Kirribilli and Milsons Point. The construction of a steam tram line from the ferry terminal up hill along Miller Street to St Leonards Park may also explain why so many terrace houses were squeezed into that part of North Sydney; in particular West Street, Ridge Street and upper Miller Street. The impact of the automobile upon North Sydney was dramatic from the second decade of the 20th century. There were at least 980 applications to Council for the construction of ‘car sheds’, ‘garages’ and ‘motor garages’ between 1914 and 1928. Many, probably most, of these were for privately-owned cars. The first garages were usually additions to existing dwellings. From the end of the 1920s, houses and unit blocks, such as the Caro Estate flats, were being designed with garages included. The effect of the Great Depression dampened demand but, in 1939, with the worst of the hardship past, there were 118 applications submitted. Transport demands prompted the two great public works projects undertaken in North Sydney, both of which resulted in the demolition of hundreds of dwellings. The Sydney Harbour Bridge, completed in 1932, provided the long-awaited fixed crossing but it also completely removed some of the more densely settled streets near Milsons Point. Some grand homes such as ‘Brisbane House’ were also knocked down. Conversely, there was a boom in the construction of flats within walking distance of the Bridge. The Bridge was built primarily with tram, train and pedestrian traffic in mind. However, within two decades of its opening, the approaches were congested with cars. The Warringah Expressway, built throughout the 1960s, was the response to this problem. It bisected the municipality and removed at least 600 homes resulting in a decline in the local population. The architecturally-significant home ‘Hanney’ was one of those lost houses. As car ownership soared in the post-war decades, it became standard to design high rise dwellings with off-street parking. In the case of the residential tower ‘Watergleam’, the work of architect D. Forsyth Evans on the Lavender Bay waterfront in 1965, this meant constructing a multi-storey above ground residents’ car park on what is now regarded as prime foreshore. Local traffic and parking were such an issue by the early 1970s that North Sydney became the test case for the right of Council to close streets in order to manage through traffic. In 1973 Supreme Court Justice Laurence Street ruled that Section 269 (1) of the Local Government Act gave Council power to ‘construct a permanent barrier across a residential road... to prevent through traffic... The Council owns the road and is charged with the care, control and management of it’. Pocket parks were planted on several of the road closures. In response to ongoing traffic congestion and pollution, the New South Wales Government’s Sydney Metropolitan Strategy (2005) aimed to increase residential densities in established suburbs, particularly where public transport links exist. North Sydney Council was directed to contribute 5,500 dwellings by 2031. Council drafted the North Sydney Residential Development Strategy in 2009 to achieve these targets. The strategy aims to meet the growing demand for ‘urban village living’, by providing more ‘1, 2 and 3 bedroom apartments’. New dwellings will be concentrated within walking distance of shops, jobs, public transport and services. Between July 2009 and 2013, 1,134 such dwellings were approved in North Sydney. |

|